|

|

|

The relative isolation of the Macedonian region in the period from the 10th to the 8th centuries BC - an isolation due to the temporary unavailability of the commercial routes from south to north - was soon overcome, and Macedonia entered upon the Archaic period as the promised land for the hundreds of colonists who came to the coasts of the Aegean from many cities in southern Greece. It was during this period that colonists from southern Greece founded Methone, Sane, Skione, Potidaia, Akanthos and many other cities-ports on the coasts of Pieria and Chalkidike.

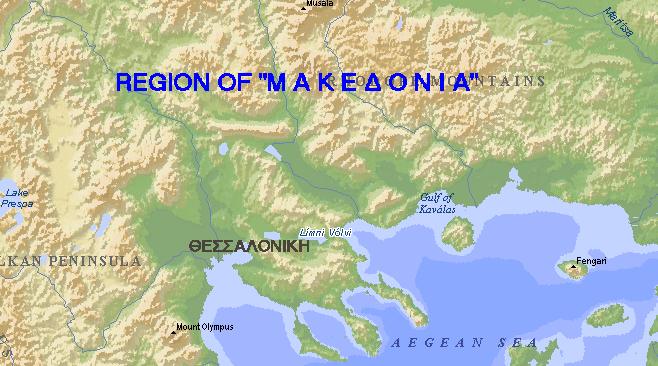

Bounded to the south by a long chain of mountain ranges -Ossa, Olympus and the Kambounian Mountains, to the west by the Pindos range, to the east by the river Strymon and then the Nestos, and to the north by Orbelos, Menoikion, Kerkine, Boras and Barnous, Macedonia was cut off from the main body of Greece, on the ramparts of Hellenism, and lived until the 6th century by the teachings of the Homeric epic.

The country was self-sufficient in products to meet basic needs (timber, cereals, game, fish, livestock, minerals) and soon became the exclusive supplier of other Greek states less blessed by nature, though at the same time it came to be the target of expansionist schemes dictated largely by economic interests. A particularly "introspective" land, with conservative customs and way of life and a social structure and political organization of a markedly archaic character, speaking a distinctive form of the Doric dialect, Macedonia took over the reigns of the Greek spirit in the 4th century BC, when the city-state was entering on its decline; revealing admirable adaptability in the face of the demands of the present and the achievements of the past, and ingenuity and boldness when confronted with the problems of the future, the country was quickly transformed into a performer of new roles, opening up new roads towards the epoch of the Hellenism of three continents.

The Macedonians were a Dorian tribe, according to the testimony of Herodotus (1, 56): "(The Dorian ethnos) ... dwelt in Pindos, where it was called Makednon; from there ... it came to the Peloponnesos, where it took the name of Dorian". And elsewhere (VIII, 43): "these (that is, the Lacedaimonians, Corinthians, Sikyonians etc.), except the people of Hermione, were of the Dorian and Makednon ethnos, and had most recently come from Erineos and Pindos and Dryopis". A Dorian tribe, then, that expanded steadily to the east of Pindos and far beyond, conquering areas in which dwelt other tribes, both Greek and non-Greek.

Byzantine lexicographers and grammarians cited examples from Macedonian in order to interpret particular features of the Homeric epics must mean that Macedonian was a very archaic dialect, and preserved features that had disappeared from the other Greek dialects; it would be absurd to suggest that these scholars, in their commentaries on the Homeric poems, might have compared them with a non-Greek language. The name given to the Macedonian cavalry - hetairoi tou basileos - "the King's Companions" - is also indicative: this occurs only in Homer, and was preserved in the historical period only amongst the Macedonians.

Although Herodotus and Thucydides, both of whom were aware of the genealogy of the Macedonian Argead or Temenids dynasty, made Perdikkas I the head of the family, and moreover at tributed to him the foundation of the state (first half of the 7th century BC), tradition records the names of kings earlier than Perdikkas (Karanos, Koinos, Tyrimmas). It was, however, only after protracted clashes with the Illyrians and the Thracians, and temporary subjection to Persian suzerainty (510-479 BC)- a period during which the Macedonians established themselves in "Lower Macedonia" - that the country acquired its definitive form and character. Through the organizational and administrative abilities of its first great leader, Alexander I, called the Philhellene, whose timely information to the southern Greeks contributed to the defeat of the Persian forces of Xerxes and Mardonios, the suzerainty of the Macedonian kingdom was extended both to the west of the lower Strymon valley and to the region of Anthemous. This brought economic benefits, including the exploitation of a number of silver mines in the area of lake Prasias (the first Macedonian coins were struck at this time), and the independent Macedonian principalities of west and north Macedonia were united around the central authority, recognizing the primacy of the Temenids king. The entry of the state into the history of southern Greece was sealed by the acceptance of Alexander I by the hellanodikai as a competitor in the Olympic games (probably those of 496 BC), in which, as we know, only Greeks were allowed to participate.

Perdikkas II, the first-born son of Alexander I, who ruled for forty years (454-412/13 BC), proved himself a skillful diplomat and a wily leader, astute in his decisions and flexible in his alliances, and set as the aim of his diplomacy the preservation of the territorial integrity of his kingdom. The completion of the internal tasks that Perdikkas II was prevented from accomplishing by the external situation fell to his successor, Archelaos I; he is credited by the ancient sources and modern scholarship alike with great sagacity and with sweeping changes in state administration, the army and commerce. During his reign, the defense of the country was organized, cultural and artistic contacts with southern Greece were extended, and the foundations were laid of a road network. A man of culture himself, the king entertained in his new palace at Pella, to where he had transferred the capital from Aigai, poets and tragedians, and even the great Euripides, who wrote his tragedies Archelaos and The Bacchae there; he invited brilliant painters - the name of Zeuxis is mentioned - and at Dion in Pieria, the Olympia of Macedonia, he founded the "Olympia", a religious festival with musical and athletic competitions in honor of Olympian Zeus and the Muses. By 399 BC, the year in which he was murdered, Archelaos I had succeeded in converting Macedonia into one of the strongest Greek powers of his period.

Philip II (359 BC), was a charismatic ruler, whose strategic genius and diplomatic ability transformed Macedonia from an insignificant and marginal country into the most important power in the Aegean and paved the way for the pan-Hellenic expedition of his son to the Orient, was an expansive leader who had the breadth of vision to usher the ancient world into the epoch of the Hellenism of three continents. During the course of his tempestuous life, he firmly established the power of the central authority in the kingdom, reorganized the army into a flexible and amazingly efficient unit, strengthened the weaker regions of his realm through movements of population, and, abroad, made Macedonia incontestably superior to the institution of the city-state which, at this precise period, was facing decline.

His unexpected death at the hands of an assassin in 336 BC, in the theater at Aigai on the very day of the marriage of his daughter Cleopatra to Alexander, the young king of the Molossians, brought to an end a brilliant career, the final aim of which was to unify the Greeks in order to exact vengeance on Persia for the invasion of 481-480 BC; Macedonia, in complete control of affairs in the Balkan peninsula, was ready to assume its new role.

His son Alexander III, was justly called the Great and passed into the pantheon of legend. And if his victories at Granikos (334 BC), Issos (333 BC), Gaugamela (331 BC) and Alexandria Nikaia (326 BC) may be thought of as sons worthy of their father, bringing about the overthrow of the mighty Persian empire and distant India, the prosperous cities founded in his name as far as the ends of the known world were his daughters - centers of the preservation and dissemination of Greek spirit, language and culture. From this world of daring and passion, of questing and contradiction the robust Hellenism of Macedonia carried theart of man to the ends of the inhabited world, bestowing poetry upon the mute and, in the infancy of mankind, instilling philosophical thought. In the libraries that were now founded from the Nile to the Indus, in the theaters that spread their wings under the skies of Baktria and Sogdiana, in the Gymnasia and the Agoras Homer suckled as yet unborn civilizations, Thucydides taught the rules of the science of history, and the great tragedians and Plato transmitted the principle of restraint and morality to absolutist regimes. Alexander's contribution to the history of the world is without doubt of the greatest importance: his period, severing the "Gordian Knot" with the Greek past, opened new horizons whose example would inspire, throughout the centuries that followed, all those leaders down to Napoleon himself who left their own mark on the course of mankind in both the East and the West.

In the immense kingdom created by Alexander's III the Great conquests in the East, Macedonia continued to be the cradle of tradition and the motherland, point of departure and return; This was the Hellenistic period. From this time to 277 BC, when Antigonos II Gonatas, the philosopher king, ascended the throne, Macedonia was the field of intense competition for the succession, was ravaged by sav age invasions by Gauls, and saw the royal tombs at Aigai dug up, cities abandoned, and celebrated generals fall ingloriously in fratricidal battles. During these fifty years, in which all the cohesion that had been won was lost, Cassander's murder of Alexander IV, son of Alexander the Great and Roxane, in 310 BC, removed the last representative of the house of the Argead dynasty, Olympias (mother of the conqueror of Asia) and Philip III Arrhidaios having already met with a Iamentable death.

Cassander (316-298/97 BC), whose cultural achievements included the foundation of Thessaloniki and Cassandreia, and after him Demetrios Poliorketes (293 BC), Pyrrhos (289/88 BC), Lysimachos and Ptolemy Keraunos (281 BC) plunged the country into a bloodbath and weakened the kingdom with their clumsy and selfish policies - some of them in the maelstrom of their tempestuous fortune-seeking lives, others in despairing attempts to dominate and acquire influence, setting as their aim the acquisition of the Macedonian crown, a title that undoubtedly conferred enormous prestige upon its bearer.

Despite all this, as is often the case in periods of political instability and demographic contrac tion, Macedonia, which at the time of Philip II had entertained some of the most famous intellects in Greece (Aristotle, Theophrastus, Speusippos), gave birth to some famous historical figures who -mainly as a result of the stability achieved under the rule of Antigonos - together with others who found protection at the royal court (Onesikritos, Marsyas, Krateros, Hieronymos, Aratos, Per saios), made Pella an important cultural center in the early and middle Hellenistic period.

It was upon this world, a world deeply influenced by Christianity, a world that slowly and surely cast off its Roman toga to don the Byzantine purple, a world sorely tried by the incursions of the Goths, the Avars, and all the others who had designs on its wealth and power, that faith in mission of the "God of mercy" erected the thousand-year empire of the East, to guide and enlighten the West. It raised the cross of the Resurrection as far afield as the banks of the Danube, in castles, in churches adorned with mosaics, and in bath-houses. Proclaiming the glory of men like Justinian I, the courage of a Heraklios, the majesty of Constantine VII Porphyrogennitus.In the face of the Avars and the Slavs, the Bulgars and the Arabs.

As the countryside was depopulated by the repeated barbarian incursions and the majority of the inhabitants sought refuge and protection in the urban centers, the cities were transformed into centers of intense commercial and cultural activity. Ports like those of Thessaloniki and Christoupolis (Kavala), with their granaries and heavy traffic in sea-faring ships, and also pros perous cities in the hinterland, such as Herakleia Lynkestis, Bargala, Serrhai and Philippoi, were adorned with brilliant buildings; their fortifications were strengthened, and their old urban tissue was abandoned as new programs of urban development were implemented (to which the destructive earthquakes of the 7th century made their contribution).

The integration of the Slavs into Byzantine society (9th century AD), the result partly of their conversion to Christianity by Cyril and Methodios and partly of the extension of Byzantine influence to the interior of the Balkans, had direct consequences for Macedonia, whose cities benefited from the peace that now prevailed. Thessaloniki evolved into an important cosmopolitan center to which flowed merchandise from East and West. Churches were erected at Kastoria and Beroia and adorned with wall-paintings in which were crystallized the basic elements of large-scale art after the triumph of Orthodoxy and the triumph of the icons.

Before 1204, the year in which Constantinople was captured by the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade, Macedonia was shaken by the upheavals and the ravaging and taking of prisoners at tending successive invasions by the Bulgarians, first under Symeon (AD 894-927) and then under Samuel (AD 989-1018), and suffered the humiliation of seeing its capital fall into the hands of Arab pirates (AD 904); almost three hundred years later, the same city, along with others (Kastoria and Serrhai) was captured after a siege by the Normans of Sicily (AD 1185). This is the reason that the 9th and 10th centuries in Macedonia have no great achievements to show in the sphere of cultural activity. A contributing factor in this was, of course, the strict centralization that informed the policy of the Macedonian dynasty. By contrast, the 11th and 12th centuries bestowed upon the north Greek administrative division men of the church and of letters, of the stature of Theophylact Hephaistos (the famous archbishop of Bulgaria, with his see at Ochrid), Michael Choumnos (metropolitan of Thessaloniki), and Eustathios Kataphloros (Metropolitan of Thessaloniki and a famous scholiast on classical texts). They contributed to a flowering of ecclesiastical architecture and church painting (Beroia, Edessa, Melenikon, Serrhai, Ayios Achillios,Thessaloniki, Mount Athos, Nerezi, Kastoria and Ochrid) of such intensity that these churches formed models for creations in other Balkan lands and as far afield as Russia and Georgia in the East and Sicily and north ern Italy in the West. Wall-paintings of the quality of Saint Panteleimon at Nerezi (1162) - a typical example of Komnenan painting, with its pronounced depiction of passion and its soft lines in the rendering of bodies, tall and elegant in their other-worldly Mannerism - or of the Latomos monastery in Thessaloniki (2nd half of the 12th century), and of the Anargyroi at Kastoria and Saint Nikolaos Kasnitzes in the same city (12th century), with their refined academic style; these are all undoubtedly points of reference for the artistic production and achievement of this age, before the empire was dismembered by the Latins and divided into king doms, baronies, and counties. And, of course, we should not forget the superb compositions of the portable icons and mural mosaics.

With the collapse of the Byzantine Empire and its dismemberment by the western crusad ers (Partitio Romaniae), the whole of Macedonia became subject to the Frankish kingdom of Thes saloniki, of which Boniface, marquis of Montferrat was appointed ruler. Despite the fact that they had prevailed, however, the new lords had to cope both with rivalries amongst themselves, and with the expansionist visions of Kalojan, the Bulgarian tzar Ioannitzes, who in 1207, the year of his death, arrived with his armies before the walls of Thessaloniki, having first captured Ser rhai and taken prisoner Baldwin, emperor of Constantinople.

The situation became increasingly confused as time went on: the Bulgarian state was con sumed by inter-dynastic quarrels and after the death of Boniface, the Frankish kingdom of Thes saloniki fell into the hands of guardians of minors: the new despot of the so-called "Despotate" of Epirus, the ambitious Theodore Komnenos Doukas An gelos (121 5-1230), brother of the founder of the state, Michael II Komnenos Doukas Angelos, systematically extended his pos sessions from Skodra in Illyria to Naupaktos (Lepanto) and, by steadily advancing his armies, succeeded in capturing the bride of the Thermaic gulf and dissolving the second largest Latin bastion in the Balkans (1224). He was defeated, however, by the Bulgarian tzar lvan Asen II in 1230, at the battle of Klokotnitsa, as a result of which his kingdom contracted to the area around Thessaloniki and shortly afterwards became subject to the rising power of the period, the em pire of Nicaea. In December 1246, loannis III Vatatzes, after a victorious advance, during which he captured Serrhai, Melenikon, Skopje, Velessa and Prilep, entered the city of saint Demetrios in triumph, and installed as its governor the Great Domestic Andronikos Palaiologos.

Caught at the center of expansionist designs, struggles for survival and domination and at tempts to recover lost prestige, Macedonia repulsed the attacks of the "Despotate" of Epirus, warded off the united armies of king Manfred of Sicily and Villehardouin, ruler of Achaia, and re captured Kastoria, Edessa, Ochrid, Skopje and Prilep, before eventually being incorporated into the Byzantine Empire, which was reconstituted on the morrow of 1261 with the capture of the Queen of Cities by Michael VIII Palaiologos.

These were ephemeral, "Pyrrhic victories", for the final page of the Byzantine epic augured the demise of a legend that had been kept alive for over a thousand years. The wretched condi tion of the empire in every sphere enabled the Serbs of Stephen Dusan to make deep advances to the south (1282.), and the mercenaries of the Catalan Company to devastate the Chalkidi ke and Mount Athos (1308.), fuelled fratricidal dynastic strife between the Palaiologoi and the Kantakouzenoi, and gave rise to social turbulence such as that provoked by the Zealots in Thessaloniki.

And as the fortresses of moral and material resistance, buffeted by the maelstrom of the times, fell one after the other on the altar of short term political planning and superstitious delusion, the myopic response to the reality of the situation brought the pagan hordes to European soil and shackled the right hand of Western civilization and Christianity. The last defenders of cities and ideals - an outstanding example of whom was the restless Manuel, governor of Thessaloniki from 1369 and subsequently emperor in Constantinople as Manuel II - felt the death rattle of Serrhai (1383) as the 14th century expired, and heard the protracted screams of Drama, Zichna, Be roia, Servia and Thessaloniki itself - once in 1395 and once, for the last time, in 1430 - with the crescent moon flying on its battlements.

Amidst the ruins of the nation, the only beacons of endurance for the enslaved population, the only points of reference to the glorious past for those who abandoned the sinking ship in good time, making their way to the West, were the books in which they took refuge in the harsh cen turies that followed - the deeply philosophical treatises, the pained verses, the inspired compo sitions of men like Thomas Magistros, Demetrios Triklinios, Theodore Kabasilas, Gregorios Pala mas, Demetrios Kydones, and the wise jurist Constantine Armenopoulos. The strikingly warm monuments of the Christian faith, created by named and anonymous mosaicists, painters of cosmic universe, architects of the undomed divine: in the Peribleptos at Ochrid (1295), in Saint Nikolaos Orphanos, in the Holy Apostles (1312-1315), in Saint Elias (at Thessaloniki), in Saint Nikolaos Kyritzes (at Kastoria), in the Church of Christ at Beroia (1315), in the Basilica of the Pro taton at Karyes on Mount Athos (end of the 13th century). In the field of myth, masters of the pal ette such as the painter Manuel Panselinos and his fellow artists Eutychios and Michael Astrapas and Georgios Kalliergis.

Faced with Ottoman predomination, the imposition of the Muslim religion by forced conversions to Islam where necessary, the arrival in Macedonia a few years after the fall of Constantinople of thousands of Jewish refugees from Spain, and the migrations of Vlach- and Slav-speaking groups, the Greek element in the Empire - the "Romaioi"(Romans) as they were called by the Turks - acquired an inner strength and rallied round the Great Idea of casting off the foreign yoke and its alien language and religion. Through the encouragement of the crusading Orthodox Church, the preservation of Greek- speaking schools, and revolutionary remittances from the Greeks of the diaspora, especially those in Italy, it kept alive its knowledge, its language and its dreams. And as time went on and the deep wounds of the first decades of slavery were forgotten, it achieved great things in commerce and trade, on the diplomatic front, in administration, and in public relations.

While ruined cities like Thessaloniki, victims of the conquest, were repopulated with peoples from every region of the Ottoman Empire, others, such as Yanitsa (Yenice), were new creations with a purely Turkish population. About the middle of the 15th century, Monastir had 185 Chris- tian families, Velessa 222 and Kastoria 938. Thessaloniki, a century later, counted 1087 fam ilies and Serrhai 357. In Drama, Naousa and Kavala, the main language spoken was Greek. The same was true of Servia, Kastoria, Naousa and Galatista. Stromnitsa, like Yanitsa, was a Turkish city. Jewish communities of some importance were to be found in Beroia, where there were equal numbers of Moslems and Christians, and in Serrhai, Monastir, Kavala and Drama. Few Slav speakers remained in the countryside of Eastern Macedonia - the remnants of Stephen Dusan's empire - though there were more in Western and the north of Central Macedonia.

The inhabitants, new and old, lived in separate communities, and were jointly responsible for the implementation of orders from the central authority, for the preservation of order and, most importantly of all, for the payment of taxes. The administration of the community was in the hands of the local aristocracy, which was permitted certain initiatives of a philanthropic or cultural na ture. This local autonomy in matters of administration also extended to the hearing by archbish ops of cases involving family and inheritance law, in accordance with Byzantine custom-law.

The administrative system of the Ottoman Empire was based on its military organization and, at the beginning of the period, the European conquests formed a single military and political district (the Eyalet of Roumelia), governed by the beyrlebey, a high-ranking official. In time, this broad unit was divided and Macedonia was broken up into smaller sections, of which Western Macedonia was assigned initially to the sanjak of Skopje and later to those of Ochrid and Monastir. By contrast, both Central and Eastern Macedonia formed separate sanjaks, with their capitals at Thessaloniki and Kavala respectively. The northern areas were assigned to the sanjak of Kyustendil.

As during the Byzantine period, cereals, apples, olives, flax and vegetables were cultivated on the fertile plains of Macedonia. As the centuries passed, tobacco, cotton and rice were ad ded to them. The creation of settlements in the mountainous areas and the intensification of stock-raising led to a reduction in the forested area. Trout from the rivers and lakes supplied the markets of Constantinople. From the numerous metal, silk and textile workshops - which owed much to the skills of the Jewish element - the empire ordered objects for daily use and also luxury goods. Goldsmiths, builders, chandlers, furriers, armourers, dyers of thread and cloth-makers in a few years turned the villages and towns in which they settled into bustling production and distribution centers. They were a source of prosperity, economic strength, building activity, and intense competition. The caravans that transported the labour and skills of these craftsmen to Vienna, Sofia and Constantinople competed with the boats from the ports of Thessaloniki and Ka vala, which discharged their cargoes at both ends of the Mediterranean. And since Hermes Kerdoos (the god of commerce) invariably walked hand in hand in Greece with Hermes Lo gios (the god of letters), as soon as the tempest of the conquest had subsided and the Greeks had gained control of trade and production, the Greek expatriates achieved great things in the free lands of Austro-Hungary, Germany, France and Italy (both before and after the fall of Con stantinople); the church assumed a leading role, supplanting the imperial authority; thirst for knowledge and the imparting of knowledge led initially to the foundation of church schools and then to the building of community educational institutions, to which flocked not only the Greeks but also the Greek-speakers of the Balkans.

Through benefactions from wealthy Macedonians such as Manolakis (1682) and Demetrios Kyritzis (1697) from Kastoria, young men were educated in Beroia, Serrhai, Naousa, Ochrid Kleisoura and Kozani. Thanks to the inspired teaching of men like Georgios Kontaris, schol arch (head of school) at Kozani (1668-1673) Georgios Parakeimenos, headmaster in the same city (1694-1707), Kallinikos Varkosis scholarch at Siatista (until 1768), and Kallinikos Manios in Beroia (about 1650), the Macedonians were able to partake of ancient and ecclesiasti cal literature and were initiated into the new achievements of science, which the intellectual pioneers of the Greek spirit were transporting from the educated West. There were many too however, who, either as refugees to the West or as willing emigrants, transmitted their own pre cious lights to the regenerated world of Europe: men like loannis Kottounios (1572-1657), lecturer in the Universities of Padua, Bologna and Pisa. Demetrios, the Patriarch's envoy to Wurtemberg (1559), and Metrophanis Kritopoulos, teacher of Greek in Venice (1627-1630).

Up until the beginning of the 19th century, though with a substantial break during the period of the Russian-Turkish confrontations (1736-38 and 1768-77), the Macedonian countryside pros pered greatly and was at the same time the scene of unprecedented building activity. New villages were constructed and existing townships extended and beautified; amidst a climate of prosperity and expanding trade, two-storey archontika (mansions) were erected at Siatista, Kozani, Kastoria, Beroia and Florina; their tiled roofs, carved wooden ceilings, and elegant built in wooden cupboards, their reception rooms lavishly painted with floral, narrative and other mo tifs, and their spacious cellars and shady court yards, all reflected the wealth of their owners and the achievements of a popular art that skill fully combined the lessons of tradition with a wide variety of borrowings from East and West.

For some time after the collapse of the Byzantine Empire, the subject Christians of Macedo nia were content to fulfill their Christian duties by using the churches that had escaped pillaging by the conquerors. As the flock steadily increased, however, and the old buildings began to feel the adverse effects of time, while the inhabitants grew more prosperous, the need to repair and beautify the houses of God under the jurisdiction of the Greek communities and also to erect new ones became inescapable. Painters from Kastoria, and then from Crete, Epirus, and Thebes, in guilds or individually, criss-crossed Macedonia from as early as the 15th century, and hymned the glories of the Orthodox faith with their palettes, some in a primitive style, others with a more academic, refined intent. Yet others from Hionades, Samarina, and Selitsa near Eratyra immortalized human vanity in secular buildings and, in the encyclopedic spirit of the age, por trayed philosophers, fantastic landscapes, the dream of the soul - Constantinople - and the vision of progress - cities of Western Europe.

And as the wheel of destiny, after many centuries, furrowed the roads of the final decision, and an unquenchable desire for freedom consumed petty interests and leveled out vainglorious vacillation, the national desire to cast of the unbearable yoke began to awaken. The year 1821 of the Uprising in the Peloponnese lit up the peaks of mount Olympus and mount Athos. Al though the repressive measures taken by the Turkish army and the seizure of hostages in Thessaloniki did not dishearten the rebels of Emmanuel Pappas and the archimandrite Kallinikos Stamatiadis on Mount Athos and Thasos, who were thirsting for action, the insurrectionaries' ignorance of military affairs and their lack of supplies, together with the ease with which the Turks were able to mobilize large armies, strangled the movement at its birth. he uprisings on Olympus and Bermion met with a similar fate, ending in the tragedy of the holocaust of Naousa.

After the liberation of southern Greece and the foundation of the free Greek state - the furthering of the Great Idea -spirits were restored and, with the invisible support of the Greek consulate in Thessaloniki, incursions began into Turkish-held Macedonian areas, to stir up arm bands. Tsamis Karatasos roused Chalkidike. So, too, did Captain Georgakis. The unfavorable turn taken by the Cretan Struggle, however, and the inability of Greeks and Serbs to make com mon cause once again prevented a general uprising of the Macedonians.

In the second half of the 19th century, the international conjunctures tended to favor the other peoples of the Balkan peninsula and international diplomacy adopted a hostile stance towards Greek affairs. With the nationalist movements of Bulgaria rivaling the Turkish rulers in their anti-Greek attitudes, Macedonia, the appleof strife of the south Balkans, strove to preserve its Greek integrity by building schools and founding educational societies; it countered Slav ex pansionism with the historical reality and the Orthodoxy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and mobilized yet again its armed hopes and the youth of Free Greece. The Macedonian Struggle was in preparation. From the ill-fated year of 1875, from the inauspicious 1897, despite the genocide and the hecatombs of victims, the marshes of Yanitsa, the mountain peaks of Gre vena, the forested ravines of Florina were transformed into pages on which, at the turn of the 20th century, men like Pavlos Melas, Constantine Mazarakis-Ainian, Spyromilios, Tellos Agapi nos (Agras) and so many others, known and anonymous, wrote the name of Macedonian re generation in their blood. In an empire on its way to collapse, despite the Young Turks' movement for renewal, and in opposition to a heavily armed, irrevocably hostile Bulgaria, with Serbia as an unreliable ally, Hellenism countered with the rights of the nation and, on 26th of October 1912, raised the flag of the cross in the capital of Macedonia, Thessaloniki. Behind it, 500 years of slavery that had not succeeded in creating slaves. Half a millennium of torture, persecution, murder, plotting, disappointment and falsification of history donned once more the blue and white and, with the sword of justice, opened the road to the modern age.